Crystal Cove’s Untold History of Japanese American Farmers

By Rehana Morita

Harvest Time (1935)

The first Japanese farmer to lease from the Irvine Company along the coast was Keichi Yamashita. The Yamashita family was one of the many Japanese American families who lived on the rich soil of Crystal Cove during the early 20th century. The families would construct homes and farm buildings on the west and east sides of the Coast Highway from Corona del Mar to the northern boundary of Laguna Beach. On the bluffs and hills of the highway, they cultivated crops such as peas, tomatoes, celery, beans and other goods. Several farms had irrigated fields, while the others depended on dry farming and the moods of the rainy season. The photograph captures the harvest of celery by farmworkers on the fields of Mr. Yamashita. He stands between two men wearing a white straw hat, and his wife is also seen wearing a white bonnet.

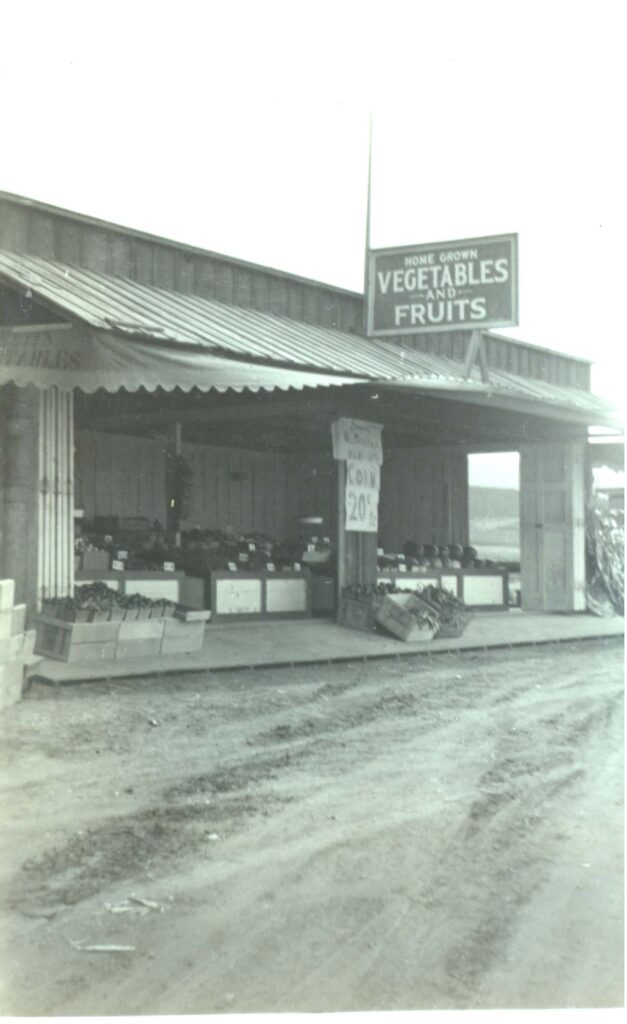

Vegetable Markets (1932)

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the anti-Japanese paranoia led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to incarcerate all people of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens, in the West Coast. Executive Order 9066 was made on February 19,1942, which forced more than 35,000 people of Japanese ancestry in the Los Angeles area to leave their homes and possessions. They were later detained in American concentration camps. On May 10, 1942, Civilian Exclusion Order No. 59 was made which forced the Japanese family tenants living between Corona del Mar and Laguna Beach to leave their farms and report to a designated area. From 1927 until their eviction in 1942, the Japanese American community of Crystal Cove sold their crops to the Los Angeles markets, and visited tourists from roadside produce stands. Many of the produce stands that the Yamashita, Miyada, Honda, and Furukawa families owned stood adjacent to their vegetable fields, facing the Pacific Ocean along the Coast Highway.

Caterpillar Tractor On The Farm (1936)

The sons of Mr. Keichi Yamashita, Harry (Hiroshi), Sam and Tak (Takashi), worked on the family farm full-time during the summers and regularly after school during the school term. Farm work had become a routine for Tak at a young age such as learning to drive cars, trucks and tractors. His favorite part of the work was feeding the plow horses, harnessing them, and working with them in the field. Tak and his family were the only Japanese Americans who were welcomed back to their farm after the war in 1946. The only reason being that his family was one of the most successful farmers in the area. Harry, the oldest of the Yamashita brothers, decided to buy his own property instead of his childhood farm because the Irvine Company wanted too much money for the lease of the land. None of the original Japanese American families returned to Crystal Cove after their incarceration at Poston in Parker, Arizona because of discrimination and nothing to go back to.

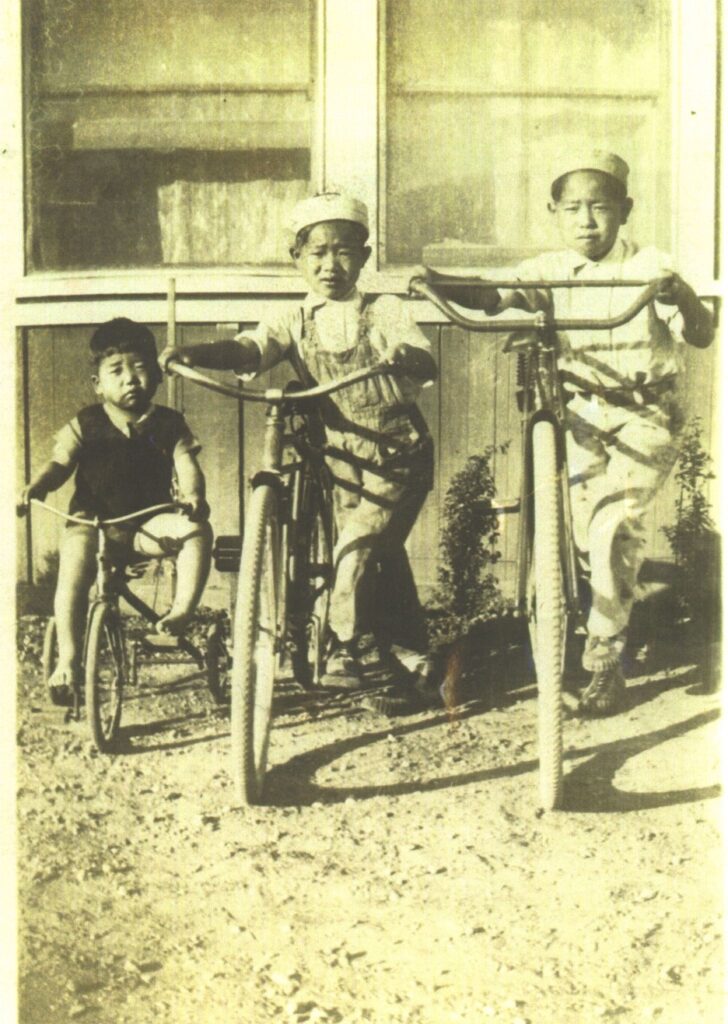

Yamashita Brothers (1932)

Tak, Sam, and Harry Yamashita pose outside their farmhouse which was designed and built by their father, Keichi Yamashita, in 1927-1928. Their homes consisted of a main house, a helper’s house, and the boy’s house. As the brothers grew older, many of their activities during leisure time were centered around the ocean. They spent many afternoons in Newport Harbor to swim, fish or hunt. Mr. Keichi Yamashita would sometimes take his sons to live theatre shows, or the brothers would go to the movies in Santa Ana and get ice cream. The parents of another Japanese American family in Crystal Cove, Unzo and Juzo Honda, began constructing a community center in 1934 to ensure that their children learn about their ancestral homeland and Japanese culture. Most of the Japanese families joined in the effort to support the construction of the center. Tom (Toshio) Honda, the son of Unzo and Juzo, stated that the official Japanese Language Schoolhouse was open on Saturdays for Japanese language classes and other activities. Teachers would come from Los Angeles or Orange County to teach language skills. Once a year, each student was required to make a speech in Japanese. The kids, however, rarely used Japanese unless they were speaking to their parents because the majority of the students in the nearby schools were white.

Kendo Uniforms (1936)

Taken at Izuo Photo Studio in Los Angeles, Keichi Yamashita pose proudly with his sons, Tak, Sam and Harry, in their kendo uniforms. Kendo is the art of Japanese samurai swordsmanship and was taught at the Japanese Language Schoolhouse. The Yamashita brothers were trained with other boys in the community by instructors from Los Angeles and Orange County. Don Miyada shared that he and a few other students participated in local kendo tournaments. Tom Honda was not interested in Japanese martial arts, so he spent more time playing football, softball and track at the Schoolhouse. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, armed soldiers entered the Schoolhouse and demanded to know what the boys were doing with the kendo equipment. Tom’s mother was afraid that the FBI might be suspicious of her family, so she then told Tom to burn all of his martial arts clothing and items. The Schoolhouse was eventually used as a barrack for the military stationed in the area after the Japanese American families were incarcerated. In 1949, the building was eventually moved to the edge above the Cove and converted into a residence.

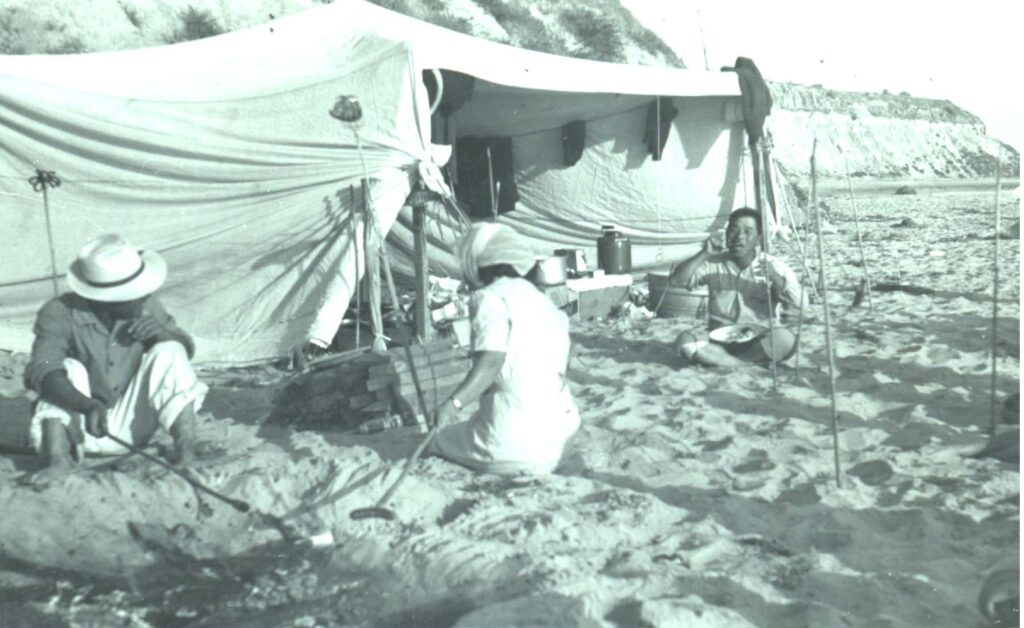

Community Picnic At The Beach (1936)

Tom Honda reminisced about the events that occurred with the local Japanese American communities of Costa Mesa and Irvine, such as a picnic at Irvine Park or softball games at the field of the Japanese Language Schoolhouse. When the harvest was thriving, the Japanese American families in the area would get together about once a year to celebrate. They would drink sake (rice wine), eat, and sing songs. The small community of Crystal Cove held events together on their own as well. During the holiday seasons, the students of the Schoolhouse would perform in an annual Christmas play. Buddhist services were also conducted regularly by ministers from Los Angeles. A community picnic was held on the beach below the bluff from the Yamashita farm, as pictured here. The families participated in activities such as swimming, sumo wrestling, and games in blindfolds. Tak Yamashita stated that his father, Keichi Yamashita, enjoyed the hot dogs that were cooked by his mother.

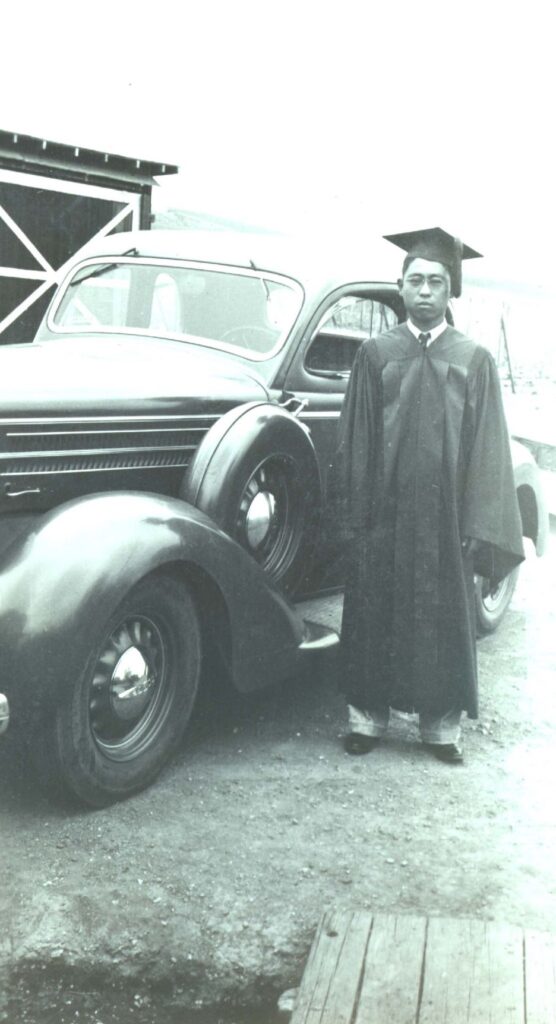

Cap & Gown (1940)

The Yamashita brothers were among those who attended public school in Laguna Beach, where the majority of his classmates were white. Tak Yamashita explained that his father wanted his American-born children to assimilate into white culture. Harry Yamashita described his high school years at Laguna Beach High School to be the best. He was involved in sports, was class treasurer and commissioner of boys’ welfare in athletics. He stated that he had many friends throughout high school, but the war changed it all for him. Before the ejection from their family’s coastal farms in 1942, many of the Japanese American high school graduates continued their education into college. Soon after Harry started his college degree at the University of California in Davis, he was called home in May 1942 to work on his family’s farm.